This is the sixth and final installment in a series of posts discussing my research into the history of the 1922 U.S. Supreme Court case of Federal Baseball Club of Baltimore v. National League, culminating in my recently released book, Baseball on Trial: The Origin of Baseball's Antitrust Exemption. Click here to read the earlier posts in the series.

Because both the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia and the U.S. Supreme Court issued published decisions in the Federal Baseball case, most sports law enthusiasts are well aware of how Baltimore's suit against the major leagues ultimately fared on appeal. Nevertheless, I was able to discover several interesting details about both proceedings during the course of my research.

For example, the court of appeals held its oral argument in Baltimore's case less than three weeks after the news that the 1919 World Series had been fixed became public. The impact that the Black Sox scandal would have on the appellate court's decision in the case was undoubtedly a concern for the major leagues. Indeed, some suspected that the court of appeals would conclude that baseball was subject to the Sherman Act because the scandal revealed the need for greater regulation of the sport. On the other hand, it is also possible that the court may have been willing to allow the American and National Leagues greater leeway to collectively centralize their operations in order to impose the type of discipline and authority that the scandal necessitated. Thus, it is ultimately unclear what impact, if any, the Black Sox scandal had on the appellate court's decision in the case.

The court of appeals eventually reversed the trial court and held that professional baseball did not constitute interstate commerce. In particular, the circuit court characterized the major leagues as being engaged in "sport" not "commerce," while stating that Baltimore's case primarily focused on the reserve clause. This latter portion of the opinion has caused some subsequent courts and commentators to believe that the suit only involved allegations concerning the reserve clause, when in reality Baltimore's claims were broader.

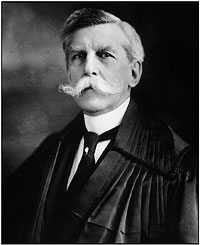

Nevertheless, the Supreme Court ultimately affirmed the court of appeals' decision in 1922. Although the Supreme Court's decision has always been understood to be unanimous, my research revealed that at least two justices -- Brandeis and McKenna -- initially cast dissenting votes. Indeed, both justices eventually wrote to Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. (pictured), the author of the majority opinion, to report that they were switching their votes so that the decision could be unanimous.

Justice Holmes's opinion in the case has regularly been misinterpreted, with many believing that it simply held that professional baseball was not sufficiently interstate in nature to fall within the Sherman Act. In reality, Holmes' decision was premised on two separate grounds. Most fundamentally, he determined that baseball was not commerce, adopting the major leagues' characterization of the term as being limited to the production or sale of tangible goods. In particular, Holmes stated that "the exhibition, although made for money would not be called trade or commerce in the commonly accepted use of those words." In addition, Holmes also determined that professional baseball was not interstate in nature because the entire source of the industry's revenue -- i.e., ticket sales to baseball exhibitions -- was generated within a single state. The transportation of players across state lines, he concluded, was thus merely "incidental."

While subsequent commentators have been highly critical of Holmes' decision in the case, my research revealed that both parts of his holding were consistent with the legal precedents in place at the time. Moreover, neither of these arguments was ever effectively rebutted by Baltimore's counsel in its briefing. Therefore, my book ultimately concludes that the Federal Baseball case, although heavily criticized today, was in fact correctly decided given the applicable legal precedents in place in 1922.

Showing posts with label Baseball on Trial. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Baseball on Trial. Show all posts

Sports Law History: The Federal Baseball Decision of 1922

7:00 AM |

Labels:

Baseball on Trial

Read User's Comments0

Sports Law History: The Federal Baseball Trial of 1919

7:00 AM |

Labels:

Baseball on Trial

This is the fifth in a series of posts discussing my research into the history of the 1922 U.S. Supreme Court case of Federal Baseball Club of Baltimore v. National League, culminating in my recently released book, Baseball on Trial: The Origin of Baseball's Antitrust Exemption. Click here to read the earlier posts in the series.

Following the dismissal of the Baltimore Terrapins' initial lawsuit in Philadelphia, the club engaged in some limited settlement negotiations with the two major leagues over the next several months. When those efforts ultimately failed, the team then opted to file a second lawsuit against the American and National Leagues in September 1917, this time in Washington, D.C. It is not entirely clear why the team elected to file suit in Washington. Baltimore likely hoped to avoid any potential prejudice from refiling the case in Philadelphia, and therefore simply opted for the closest city hosting a major league team (for service of process reasons).

Because the trial court never issued a formal written opinion in the case, relatively little has been known about the lower court proceedings in the Federal Baseball suit. Baltimore's complaint was divided into two primary sets of allegations, the first dealing with the major leagues' monopolization of the professional baseball industry from 1903-1915, and the second contesting the ultimate destruction of the Federal League in 1915, both of which the team believed constituted violations of both federal antitrust and state law. In particular, Baltimore alleged that the American and National Leagues had monopolized the industry in various ways, not only by securing their claim to nearly all professional players through the use of the reserve clause (thereby tying each player to his current team for the entire length of his career), but also by guaranteeing all major league teams exclusive control over their geographic territories. This latter aspect of the team's case has often gone largely overlooked in modern treatments of the dispute, as courts and scholars have at times believed the case simply involved monopolization allegations relating to the reserve clause.

Due to the Washington court's congested docket, the suit would not be called for trial until March 1919. The parties eventually staged a fourteen day jury trial, featuring testimony from a variety of baseball executives (including legendary Philadelphia A's manager Connie Mack) and former players. Baltimore's newly retained legal counsel was able to present a much stronger case on the team's behalf than was asserted in the Philadelphia suit, emphasizing not only the dissolution of the Federal League in 1915, but also the major leagues' consistent monopolization of the industry for years prior.

Following the completion of the witness testimony, presiding judge Wendell Stafford allowed each side to present dueling motions for directed verdict, with both parties asserting that the undisputed evidence from the trial warranted a verdict in their favor. These arguments ultimately turned on the question of jurisdiction, as the parties disputed whether professional baseball constituted interstate commerce, and thus was subject to federal antitrust law. Baltimore's counsel stressed the fact that major league teams were spread across a number of different states, necessitating the transportation of both players and equipment across state lines, as proof that the leagues were engaged in interstate commerce. The team's counsel was so convinced of the strength of their argument that they opted to voluntarily waive Baltimore's claims arising under state law, resting its case entirely on the applicability of federal antitrust law. This decision would prove to be a critical mistake in hindsight.

Conversely, the American and National Leagues' counsel, George Wharton Pepper, argued that the business of professional baseball did not constitute commerce under the prevailing judicial definition in place at the time. In particular, Pepper stressed a series of precedents holding that commerce only involved the production or sale of tangible goods. Because the major leagues produced no tangible products themselves, but instead merely sold tickets to ephemeral exhibitions of baseball (games that were staged entirely in one state, no less), he did not believe that professional baseball was engaged in interstate commerce. Consequently, Pepper asserted, baseball could not be regulated under Congress's interstate commerce powers and therefore not subject to federal antitrust law.

Judge Stafford adopted the plaintiff's view of the law. He ruled from the bench that the major leagues were engaged in interstate commerce, and that they had illegally monopolized the industry in violation of the Sherman Act. Stafford indicated that he was not entirely convinced that this determination was correct, however, suggesting that he was ruling in Baltimore's favor in part to avoid the potential need for a retrial, thereby allowing the already empaneled jury to resolve the remaining factual issues (namely, whether Baltimore had itself been harmed by the major league's monopoly, and, if so, what the extent of its damages were). Had Stafford instead ruled in the major leagues' favor and dismissed the suit, only to have his decision overturned on appeal, the parties would then have had to stage a new trial to determine the remaining factual issues in dispute.

The jury ultimately returned a verdict awarding Baltimore $80,000 in damages (subsequently trebled to $240,000), much less than the $300,000 in damages the team had sought, but a significant victory nonetheless. The major leagues, of course, immediately vowed to appeal the decision, and were confident that their position would ultimately be adopted by a higher court. Their prediction eventually proved correct.

Following the dismissal of the Baltimore Terrapins' initial lawsuit in Philadelphia, the club engaged in some limited settlement negotiations with the two major leagues over the next several months. When those efforts ultimately failed, the team then opted to file a second lawsuit against the American and National Leagues in September 1917, this time in Washington, D.C. It is not entirely clear why the team elected to file suit in Washington. Baltimore likely hoped to avoid any potential prejudice from refiling the case in Philadelphia, and therefore simply opted for the closest city hosting a major league team (for service of process reasons).

Because the trial court never issued a formal written opinion in the case, relatively little has been known about the lower court proceedings in the Federal Baseball suit. Baltimore's complaint was divided into two primary sets of allegations, the first dealing with the major leagues' monopolization of the professional baseball industry from 1903-1915, and the second contesting the ultimate destruction of the Federal League in 1915, both of which the team believed constituted violations of both federal antitrust and state law. In particular, Baltimore alleged that the American and National Leagues had monopolized the industry in various ways, not only by securing their claim to nearly all professional players through the use of the reserve clause (thereby tying each player to his current team for the entire length of his career), but also by guaranteeing all major league teams exclusive control over their geographic territories. This latter aspect of the team's case has often gone largely overlooked in modern treatments of the dispute, as courts and scholars have at times believed the case simply involved monopolization allegations relating to the reserve clause.

Due to the Washington court's congested docket, the suit would not be called for trial until March 1919. The parties eventually staged a fourteen day jury trial, featuring testimony from a variety of baseball executives (including legendary Philadelphia A's manager Connie Mack) and former players. Baltimore's newly retained legal counsel was able to present a much stronger case on the team's behalf than was asserted in the Philadelphia suit, emphasizing not only the dissolution of the Federal League in 1915, but also the major leagues' consistent monopolization of the industry for years prior.

Following the completion of the witness testimony, presiding judge Wendell Stafford allowed each side to present dueling motions for directed verdict, with both parties asserting that the undisputed evidence from the trial warranted a verdict in their favor. These arguments ultimately turned on the question of jurisdiction, as the parties disputed whether professional baseball constituted interstate commerce, and thus was subject to federal antitrust law. Baltimore's counsel stressed the fact that major league teams were spread across a number of different states, necessitating the transportation of both players and equipment across state lines, as proof that the leagues were engaged in interstate commerce. The team's counsel was so convinced of the strength of their argument that they opted to voluntarily waive Baltimore's claims arising under state law, resting its case entirely on the applicability of federal antitrust law. This decision would prove to be a critical mistake in hindsight.

Conversely, the American and National Leagues' counsel, George Wharton Pepper, argued that the business of professional baseball did not constitute commerce under the prevailing judicial definition in place at the time. In particular, Pepper stressed a series of precedents holding that commerce only involved the production or sale of tangible goods. Because the major leagues produced no tangible products themselves, but instead merely sold tickets to ephemeral exhibitions of baseball (games that were staged entirely in one state, no less), he did not believe that professional baseball was engaged in interstate commerce. Consequently, Pepper asserted, baseball could not be regulated under Congress's interstate commerce powers and therefore not subject to federal antitrust law.

Judge Stafford adopted the plaintiff's view of the law. He ruled from the bench that the major leagues were engaged in interstate commerce, and that they had illegally monopolized the industry in violation of the Sherman Act. Stafford indicated that he was not entirely convinced that this determination was correct, however, suggesting that he was ruling in Baltimore's favor in part to avoid the potential need for a retrial, thereby allowing the already empaneled jury to resolve the remaining factual issues (namely, whether Baltimore had itself been harmed by the major league's monopoly, and, if so, what the extent of its damages were). Had Stafford instead ruled in the major leagues' favor and dismissed the suit, only to have his decision overturned on appeal, the parties would then have had to stage a new trial to determine the remaining factual issues in dispute.

The jury ultimately returned a verdict awarding Baltimore $80,000 in damages (subsequently trebled to $240,000), much less than the $300,000 in damages the team had sought, but a significant victory nonetheless. The major leagues, of course, immediately vowed to appeal the decision, and were confident that their position would ultimately be adopted by a higher court. Their prediction eventually proved correct.

Sports Law History: The Baltimore Federals' Largely Forgotten Philadelphia Lawsuit

7:00 AM |

Labels:

Baseball on Trial

This is the fourth in a series of posts discussing my research into the history of the 1922 U.S. Supreme Court case of Federal Baseball Club of Baltimore v. National League, culminating in my recently released book, Baseball on Trial: The Origin of Baseball's Antitrust Exemption. Click here to read the earlier posts in the series.

Students of baseball history, and sports law enthusiasts, are likely aware that the Federal League's Baltimore Terrapins opted out of the Federal League-Major League peace agreement of December 1915, with the team instead electing to file its own antitrust lawsuit against the American and National Leagues. That litigation, of course, ultimately culminated in the Supreme Court's 1922 decision giving rise to baseball's infamous antitrust exemption. What fewer people realize, however, is that the suit that eventually made its way to the Supreme Court -- following trial court proceedings in Washington, D.C. -- was not the Baltimore club's first lawsuit against the major leagues.

Indeed, a few months after the Federal League-Major League peace agreement, the Baltimore Terrapins filed suit against the American and National Leagues in the federal district court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. The suit charged the major leagues with violating both Sections 1 and 2 of the Sherman Act, not only by conspiring to drive the Federal League out of business throughout its short life-span, but also by reestablishing monopoly conditions in professional baseball through the 1915 peace agreement.

Unfortunately for Baltimore, this initial lawsuit appeared to be ill-fated from the start. Shortly before trial was scheduled to begin in June 1917, the team's lead attorney, and noted antitrust lawyer, William Glasgow became unable to try the suit as planned for unknown reasons. Consequently, the club's general counsel, Stuart Janney, was forced to step in at the last minute to try the case himself on behalf of the team. Janney struggled to effectively present such a complex case on short notice, and after three-and-a-half days of largely unproductive testimony, he abruptly and unexpectedly announced that the plaintiff was resting its case.

The bad news continued to mount for Baltimore early in the presentation of the defense's case, when the major league's first witness, National League President John Tener, testified that he was in possession of a transcript of the December 1915 peace negotiations between the Federal League and the major leagues. Baltimore's counsel had been completely unaware of the existence of such a transcript, and upon reviewing the document that night determined that it largely undermined the team's case. In particular, the transcript showed that Baltimore had been represented during the negotiations by two of its corporate executives, including its general counsel Janney, who had failed to object when Federal League officials made several unfavorable representations during the peace negotiations. Because Janney had predominately focused his presentation of evidence on the illegality of the 1915 peace agreement, he believed the transcript largely undermined Baltimore's case, not only by suggesting that the team had acquiesced to the Federal League's dissolution, but also insofar as it placed him as an important witness to key events in the trial.

As a result, Janney stunned the crowd gathered in the courtroom at the beginning of the fifth day of the trial by announcing that the plaintiff was voluntarily dismissing its case. Although some press reports speculated that a settlement must in the works, both sides insisted that that was not the case. Indeed, despite withdrawing their suit, Baltimore's counsel sent a letter to the major leagues' attorneys that afternoon maintaining that the team continued to believe its rights had been violated. Consequently, Baltimore would eventually file a second, broader antitrust suit against the major leagues several months later, this time in Washington, D.C.

Students of baseball history, and sports law enthusiasts, are likely aware that the Federal League's Baltimore Terrapins opted out of the Federal League-Major League peace agreement of December 1915, with the team instead electing to file its own antitrust lawsuit against the American and National Leagues. That litigation, of course, ultimately culminated in the Supreme Court's 1922 decision giving rise to baseball's infamous antitrust exemption. What fewer people realize, however, is that the suit that eventually made its way to the Supreme Court -- following trial court proceedings in Washington, D.C. -- was not the Baltimore club's first lawsuit against the major leagues.

Indeed, a few months after the Federal League-Major League peace agreement, the Baltimore Terrapins filed suit against the American and National Leagues in the federal district court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. The suit charged the major leagues with violating both Sections 1 and 2 of the Sherman Act, not only by conspiring to drive the Federal League out of business throughout its short life-span, but also by reestablishing monopoly conditions in professional baseball through the 1915 peace agreement.

Unfortunately for Baltimore, this initial lawsuit appeared to be ill-fated from the start. Shortly before trial was scheduled to begin in June 1917, the team's lead attorney, and noted antitrust lawyer, William Glasgow became unable to try the suit as planned for unknown reasons. Consequently, the club's general counsel, Stuart Janney, was forced to step in at the last minute to try the case himself on behalf of the team. Janney struggled to effectively present such a complex case on short notice, and after three-and-a-half days of largely unproductive testimony, he abruptly and unexpectedly announced that the plaintiff was resting its case.

The bad news continued to mount for Baltimore early in the presentation of the defense's case, when the major league's first witness, National League President John Tener, testified that he was in possession of a transcript of the December 1915 peace negotiations between the Federal League and the major leagues. Baltimore's counsel had been completely unaware of the existence of such a transcript, and upon reviewing the document that night determined that it largely undermined the team's case. In particular, the transcript showed that Baltimore had been represented during the negotiations by two of its corporate executives, including its general counsel Janney, who had failed to object when Federal League officials made several unfavorable representations during the peace negotiations. Because Janney had predominately focused his presentation of evidence on the illegality of the 1915 peace agreement, he believed the transcript largely undermined Baltimore's case, not only by suggesting that the team had acquiesced to the Federal League's dissolution, but also insofar as it placed him as an important witness to key events in the trial.

As a result, Janney stunned the crowd gathered in the courtroom at the beginning of the fifth day of the trial by announcing that the plaintiff was voluntarily dismissing its case. Although some press reports speculated that a settlement must in the works, both sides insisted that that was not the case. Indeed, despite withdrawing their suit, Baltimore's counsel sent a letter to the major leagues' attorneys that afternoon maintaining that the team continued to believe its rights had been violated. Consequently, Baltimore would eventually file a second, broader antitrust suit against the major leagues several months later, this time in Washington, D.C.

Sports Law History: Judge Landis and the Federal League Antitrust Suit of 1915

10:00 AM |

Labels:

Baseball on Trial

This is the third in a series of posts discussing my research into the history of the 1922 U.S. Supreme Court case of Federal Baseball Club of Baltimore v. National League, culminating in my recently released book, Baseball on Trial: The Origin of Baseball's Antitrust Exemption. Click here to read the earlier posts in the series.

Aside from the Supreme Court's decision in the Federal Baseball suit itself, perhaps the most famous legal development arising out of the Federal League challenge was the antitrust suit the Federals filed in 1915 against the major leagues in the Chicago federal court of Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis (pictured). While many sports law enthusiasts were generally aware of the Federal League's antitrust suit, and Landis's involvement in it, prior to my research little was known about the actual proceedings themselves. Fortunately, most of the original court papers, as well as a transcript of the four-day hearing held before Judge Landis in January 1915, have been preserved by the National Baseball Hall of Fame Research Library in Cooperstown, New York. These materials serve as the basis for the fourth chapter in my book, documenting the Federal League's antitrust lawsuit against the two major leagues.

The Federal League filed its suit on January 5, 1915. The complaint alleged that the American and National Leagues had illegally monopolized the professional baseball industry in violation of both federal and state antitrust law, and had also illegally conspired to destroy the Federal League in violation of state law. The league asked the court to issue an injunction preventing the major leagues from continuing to coordinate their activities under the so-called National Agreement (the document governing professional baseball at the time) and from continuing to interfere with the Federal League's operations (such as by filing any new lawsuits against Federal League players).

Shortly after the suit was filed, Judge Landis scheduled a hearing in the case for January 20th to decide whether to grant the Federal League a preliminary injunction. The first day of the hearing was a significant event, as well over a thousand Chicago-based baseball fans reportedly flocked to the courthouse in hopes of snagging a seat to watch the proceedings. The parties ultimately spent four full days arguing before Judge Landis, with the issue of jurisdiction taking center stage throughout much of the proceedings. In particular, the major leagues alleged that they were not subject to federal or state antitrust law insofar as they did not consider baseball to be commerce. Relying on traditional definitions in place at the time limiting the term "commerce" to the production or sale of physical goods, the leagues argued that they did not themselves produce or sell anything tangible, but instead simply staged intangible amusements, beyond the scope of antitrust law. The Federal League, of course, disputed this characterization, contending that baseball was commerce insofar as the leagues paid to transport both players and equipment across state lines in order to stage their exhibitions.

Although the parties and media anticipated that Judge Landis would issue a ruling in the suit within a few weeks, he ultimately withheld his opinion for over a year. Landis would later explain his inaction by stating that if had he had issued an order it would have severely damaged both sides of the dispute, and potentially the sport itself, and therefore that he believed deferring his decision was the most prudent course of action. In the meantime, all three leagues struggled financially throughout the 1915 season, in the face of both an economic recession and the on-set of World War I. Consequently, both sides agreed to a truce in December 1915. Under the terms of the agreement, the Federal League agreed to cease its operations in exchange for payments totaling over $450,000 from the major leagues. In addition, two Federal League owners were allowed to purchase existing major league clubs (the Chicago Cubs and St. Louis Browns). While the terms of the deal satisfied seven of the eight Federal League teams, the owners of the league's Baltimore Terrapins objected to the agreement on the grounds that they did not receive anything under the deal. Despite the Terrapins' protests, the settlement was ultimately ratified, and as a result the Baltimore club subsequently pursued its own antitrust litigation, eventually culminating in the Supreme Court's Federal Baseball decision.

Judge Landis, of course, would later become baseball's first commissioner in 1920 in the aftermath of the fixing of the 1919 World Series (i.e., the so-called Black Sox scandal). Subsequent scholars have been largely critical of Landis's involvement in the Federal League's antitrust suit, believing that the judge was predisposed to side with the major leagues. For example, these scholars cite abbreviated press reports in which, at one point in the hearing, Landis declared that any "blow at this thing called baseball ... will be regarded by this court as a blow at a National institution." However, as my research reveals, when the exchange is read in its entirety Landis was actually admonishing major league baseball's attorney by explaining that one's personal affection for the game of baseball was irrelevant to the question of whether the major leagues had violated the law.

Moreover, while it is certainly true that Landis could have issued a ruling much sooner in the case, ultimately the delay appears to have had a relatively insignificant impact on the continued viability of the Federal League. Indeed, by the end of the four-day hearing the Federals had simplified their request for immediate injunctive relief to simply an order preventing the major leagues from interfering with the Federal League's players or denigrating the league in the press. With a few minor exceptions, the major leagues largely acceded to these requests throughout 1915 despite the lack of a formal injunction. Therefore, even if Landis had issued a ruling on a more timely basis it is far from certain whether it would have significantly helped the Federal League.

Thus, despite baseball fans' general awareness of the Federal League's 1915 antitrust suit and Judge Landis's involvement in the litigation, I nevertheless believe my book will uncover a number of important new details about the proceedings.

Aside from the Supreme Court's decision in the Federal Baseball suit itself, perhaps the most famous legal development arising out of the Federal League challenge was the antitrust suit the Federals filed in 1915 against the major leagues in the Chicago federal court of Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis (pictured). While many sports law enthusiasts were generally aware of the Federal League's antitrust suit, and Landis's involvement in it, prior to my research little was known about the actual proceedings themselves. Fortunately, most of the original court papers, as well as a transcript of the four-day hearing held before Judge Landis in January 1915, have been preserved by the National Baseball Hall of Fame Research Library in Cooperstown, New York. These materials serve as the basis for the fourth chapter in my book, documenting the Federal League's antitrust lawsuit against the two major leagues.

The Federal League filed its suit on January 5, 1915. The complaint alleged that the American and National Leagues had illegally monopolized the professional baseball industry in violation of both federal and state antitrust law, and had also illegally conspired to destroy the Federal League in violation of state law. The league asked the court to issue an injunction preventing the major leagues from continuing to coordinate their activities under the so-called National Agreement (the document governing professional baseball at the time) and from continuing to interfere with the Federal League's operations (such as by filing any new lawsuits against Federal League players).

Shortly after the suit was filed, Judge Landis scheduled a hearing in the case for January 20th to decide whether to grant the Federal League a preliminary injunction. The first day of the hearing was a significant event, as well over a thousand Chicago-based baseball fans reportedly flocked to the courthouse in hopes of snagging a seat to watch the proceedings. The parties ultimately spent four full days arguing before Judge Landis, with the issue of jurisdiction taking center stage throughout much of the proceedings. In particular, the major leagues alleged that they were not subject to federal or state antitrust law insofar as they did not consider baseball to be commerce. Relying on traditional definitions in place at the time limiting the term "commerce" to the production or sale of physical goods, the leagues argued that they did not themselves produce or sell anything tangible, but instead simply staged intangible amusements, beyond the scope of antitrust law. The Federal League, of course, disputed this characterization, contending that baseball was commerce insofar as the leagues paid to transport both players and equipment across state lines in order to stage their exhibitions.

Although the parties and media anticipated that Judge Landis would issue a ruling in the suit within a few weeks, he ultimately withheld his opinion for over a year. Landis would later explain his inaction by stating that if had he had issued an order it would have severely damaged both sides of the dispute, and potentially the sport itself, and therefore that he believed deferring his decision was the most prudent course of action. In the meantime, all three leagues struggled financially throughout the 1915 season, in the face of both an economic recession and the on-set of World War I. Consequently, both sides agreed to a truce in December 1915. Under the terms of the agreement, the Federal League agreed to cease its operations in exchange for payments totaling over $450,000 from the major leagues. In addition, two Federal League owners were allowed to purchase existing major league clubs (the Chicago Cubs and St. Louis Browns). While the terms of the deal satisfied seven of the eight Federal League teams, the owners of the league's Baltimore Terrapins objected to the agreement on the grounds that they did not receive anything under the deal. Despite the Terrapins' protests, the settlement was ultimately ratified, and as a result the Baltimore club subsequently pursued its own antitrust litigation, eventually culminating in the Supreme Court's Federal Baseball decision.

Judge Landis, of course, would later become baseball's first commissioner in 1920 in the aftermath of the fixing of the 1919 World Series (i.e., the so-called Black Sox scandal). Subsequent scholars have been largely critical of Landis's involvement in the Federal League's antitrust suit, believing that the judge was predisposed to side with the major leagues. For example, these scholars cite abbreviated press reports in which, at one point in the hearing, Landis declared that any "blow at this thing called baseball ... will be regarded by this court as a blow at a National institution." However, as my research reveals, when the exchange is read in its entirety Landis was actually admonishing major league baseball's attorney by explaining that one's personal affection for the game of baseball was irrelevant to the question of whether the major leagues had violated the law.

Moreover, while it is certainly true that Landis could have issued a ruling much sooner in the case, ultimately the delay appears to have had a relatively insignificant impact on the continued viability of the Federal League. Indeed, by the end of the four-day hearing the Federals had simplified their request for immediate injunctive relief to simply an order preventing the major leagues from interfering with the Federal League's players or denigrating the league in the press. With a few minor exceptions, the major leagues largely acceded to these requests throughout 1915 despite the lack of a formal injunction. Therefore, even if Landis had issued a ruling on a more timely basis it is far from certain whether it would have significantly helped the Federal League.

Thus, despite baseball fans' general awareness of the Federal League's 1915 antitrust suit and Judge Landis's involvement in the litigation, I nevertheless believe my book will uncover a number of important new details about the proceedings.

Sports Law History: The Federal League as the First Single Entity League

7:00 AM |

Labels:

Baseball on Trial

This is the second in a series of posts discussing my research into the history of the 1922 U.S. Supreme Court case of Federal Baseball Club of Baltimore v. National League, culminating in my recently released book, Baseball on Trial: The Origin of Baseball's Antitrust Exemption. Click here to read the earlier posts in the series.

Those who are well familiar with the Supreme Court's decision in the Federal Baseball case know that the lawsuit evolved out of the Federal League challenge to the American and National Leagues in 1914 and 1915. One potentially interesting aspect of the Federal League's operations that I discovered during the course of my research was that the league was arguably structured as the first single-entity professional sports league. While much has been made in recent years of the so-called single-entity defense under Section One of the Sherman Act -- ultimately culminating in the Supreme Court's 2010 decision rejecting the theory in American Needle v. National Football League -- the Federal League appears to have been well ahead of its time, structuring its operations in such a manner that may have arguably allowed it to avoid the Section One scrutiny that the existing professional leagues' operations are typically subject to today.

Founded in 1913, the Federal League was organized as a for-profit, Indiana corporation. More importantly, the league exerted significant control over its member teams. For instance, under the terms of the league's franchise agreement, the Federal League could seize control of any team if it violated any league rule. Indeed, the Federal League exercised this authority on at least one occasion, declaring that the Kansas City Packers franchise had been forfeited to the league in February 1915 due to its failure to raise sufficient capital for the upcoming season (the history of the litigation resulting from this seizure is detailed in my forthcoming law review article, Insolvent Professional Sports Teams: A Historical Case Study). In contrast, the NFL Constitution only allows the league to terminate a franchise in instances where the team (i) files for bankruptcy, (ii) disbands in mid-season, or (iii) permanently goes out of business. Thus, the central Federal League office possessed greater authority over its individual franchises than is typically the case in professional sports leagues today.

Meanwhile, although each of the Federal League's eight teams owed 1/8th of the league entity's corporate stock, the league required that these shares be assigned back to it in return for the grant of a franchise. Similarly, the league also required that each franchise assign its stadium lease to the league, so that teams could not unilaterally desert the league to join the major leagues (or if they did, they would at least no longer have anywhere to play).

Admittedly, this structure may not have been enough for a modern day court to hold that the Federal League operated as a single economic actor in the marketplace, and thus was a single-entity beyond the scope of Section One after American Needle. This is especially true given that each Federal League team was independently owned and operated, and had a direct voice in the league's operation by holding a seat on the league's Board of Directors. In many respects, the Federal League structure was thus roughly analogous to that originally adopted by Major League Soccer. Despite initially convincing a federal district court that it was a single-entity, MLS's bid for Section One immunity ultimately failed at the First Circuit Court of Appeals. Nevertheless, a league adopting the Federal League's structure today would likely be able to stake a stronger claim to single-entity status than can many of our existing professional sports leagues.

Those who are well familiar with the Supreme Court's decision in the Federal Baseball case know that the lawsuit evolved out of the Federal League challenge to the American and National Leagues in 1914 and 1915. One potentially interesting aspect of the Federal League's operations that I discovered during the course of my research was that the league was arguably structured as the first single-entity professional sports league. While much has been made in recent years of the so-called single-entity defense under Section One of the Sherman Act -- ultimately culminating in the Supreme Court's 2010 decision rejecting the theory in American Needle v. National Football League -- the Federal League appears to have been well ahead of its time, structuring its operations in such a manner that may have arguably allowed it to avoid the Section One scrutiny that the existing professional leagues' operations are typically subject to today.

Founded in 1913, the Federal League was organized as a for-profit, Indiana corporation. More importantly, the league exerted significant control over its member teams. For instance, under the terms of the league's franchise agreement, the Federal League could seize control of any team if it violated any league rule. Indeed, the Federal League exercised this authority on at least one occasion, declaring that the Kansas City Packers franchise had been forfeited to the league in February 1915 due to its failure to raise sufficient capital for the upcoming season (the history of the litigation resulting from this seizure is detailed in my forthcoming law review article, Insolvent Professional Sports Teams: A Historical Case Study). In contrast, the NFL Constitution only allows the league to terminate a franchise in instances where the team (i) files for bankruptcy, (ii) disbands in mid-season, or (iii) permanently goes out of business. Thus, the central Federal League office possessed greater authority over its individual franchises than is typically the case in professional sports leagues today.

Meanwhile, although each of the Federal League's eight teams owed 1/8th of the league entity's corporate stock, the league required that these shares be assigned back to it in return for the grant of a franchise. Similarly, the league also required that each franchise assign its stadium lease to the league, so that teams could not unilaterally desert the league to join the major leagues (or if they did, they would at least no longer have anywhere to play).

Admittedly, this structure may not have been enough for a modern day court to hold that the Federal League operated as a single economic actor in the marketplace, and thus was a single-entity beyond the scope of Section One after American Needle. This is especially true given that each Federal League team was independently owned and operated, and had a direct voice in the league's operation by holding a seat on the league's Board of Directors. In many respects, the Federal League structure was thus roughly analogous to that originally adopted by Major League Soccer. Despite initially convincing a federal district court that it was a single-entity, MLS's bid for Section One immunity ultimately failed at the First Circuit Court of Appeals. Nevertheless, a league adopting the Federal League's structure today would likely be able to stake a stronger claim to single-entity status than can many of our existing professional sports leagues.

Sports Law History: The Federal League Litigation of 1914

7:00 AM |

Labels:

Baseball on Trial

This is the first in a series of posts discussing my research into the history of the 1922 U.S. Supreme Court case of Federal Baseball Club of Baltimore v. National League, culminating in my recently released book, Baseball on Trial: The Origin of Baseball's Antitrust Exemption.

One hundred years ago, professional baseball was in a state of turmoil. The two major leagues, the American and National, were facing a challenge to their supremacy from the rival Federal League. After completing its initial season in 1913 employing mostly semi-professional and former pro players, the Federal League announced its intentions to elevate itself to major league status in 1914 by signing major league players away from their current clubs. The Federal League believed it could do this based on advice from its legal counsel, who had determined that the existing standard major league player contract was legally unenforceable due to two provisions: the reserve clause and the ten-day release provision. The reserve clause assigned each team the automatic right to renew its players' contracts for the following season, effectively tying players to their current teams for the entire length of their careers. Meanwhile, the ten-day release provision allowed teams to release their players for any reason at all simply by providing them with ten days notice.

The Federal League's attorneys believed that these two provisions, taken in combination, rendered the players' contracts legally unenforceable due to a lack of mutuality, insofar as they believed it was unfair to force a player to work for a single team for his entire career when the team itself was bound to the player for no more than ten days at a time. The Federal League's position was supported by several legal decisions arising out of the so-called Players' League challenge of 1890, in which courts refused to enforce the reserve clause in players' contracts. See Metropolitan Exhibition Co. v. Ward, 9 N. Y. Supp. 779 (Sup. Ct. 1890); Metropolitan Exhibition Co. v. Ewing, 42 Fed. 198 (C. C. S. D. N. Y. 1890). Based on this legal theory, the Federal League successfully persuaded approximately 50 major league players to sign with it during the 1913-14 off-season.

The major leagues fought back by aggressively recruiting the defecting players back into their fold, often offering the players significant raises. Ultimately, thirteen different lawsuits were filed between the two sides in 1914, as the parties sought injunctions to prevent their players from jumping back and forth between the leagues. While devoted students of baseball legal history may have already been aware of several of these cases, including Cincinnati Exhibition Co. v. Marsans, 216 F. 269 (E.D. Mo. 1914), Weeghman v. Killefer, 215 F. 168 (W.D. Mich. 1914), and American League Baseball Club of Chicago v. Chase, 149 N.Y.S. 6 (Erie County Sup. Ct. 1914), others had been largely forgotten prior to my research.

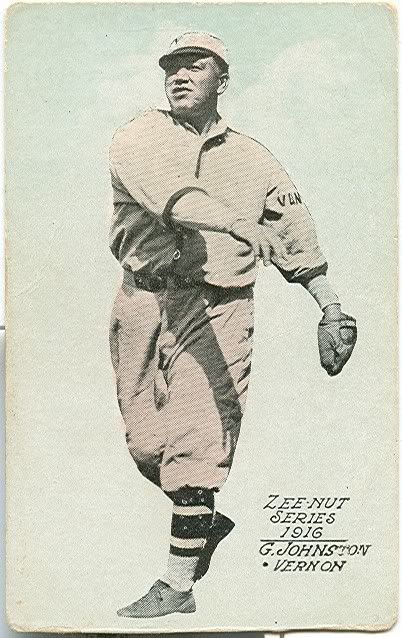

For example, one of the most significant cases of the year involved pitcher George "Chief" Johnson (pictured), who defected to the Federal League in April 1914 following a dispute with his prior team, the Cincinnati Reds. The Reds immediately secured a temporary injunction in Illinois state court to prevent Johnson from making his Federal League debut in Chicago during the inaugural game at Weeghman Park, better known today as Wrigley Field. By the time Cincinnati's attorneys reached the ballpark, however, the game had already begun, so Johnson was served with the court papers when walking off the field after the second inning.

The court eventually held a hearing several weeks later to decide whether to issue a permanent injunction preventing Johnson from playing for his new team. The Federal League was so confident it would ultimately prevail in the Johnson case that it reportedly arranged for as many as thirty-seven major league players to jump to the new league should it receive a favorable decision from the Chicago court. Unfortunately for the Federals, however, the state court judge issued a permanent injunction on June 3, 1914, upholding the standard player contract Johnson had signed with the Reds, on the basis that it must have been fair in light of the number of players who had voluntarily agreed its terms. Although this decision would be overturned on appeal several weeks later -- allowing Johnson to resume his Federal League career -- the damage had been done, as the Federal League's planned raid of the major leagues fell apart following the trial court decision.

While the initial decision by the Johnson court was a significant set-back for the Federal League, the parties ultimately battled to a draw in their 1914 litigation efforts, with both sides winning several important decisions. Perhaps more significantly, these lawsuits also set the stage for the next major phase of the Federal League's legal challenge to the major leagues, namely the federal antitrust lawsuit it filed with Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis in 1915 (to be discussed in my next post).

One hundred years ago, professional baseball was in a state of turmoil. The two major leagues, the American and National, were facing a challenge to their supremacy from the rival Federal League. After completing its initial season in 1913 employing mostly semi-professional and former pro players, the Federal League announced its intentions to elevate itself to major league status in 1914 by signing major league players away from their current clubs. The Federal League believed it could do this based on advice from its legal counsel, who had determined that the existing standard major league player contract was legally unenforceable due to two provisions: the reserve clause and the ten-day release provision. The reserve clause assigned each team the automatic right to renew its players' contracts for the following season, effectively tying players to their current teams for the entire length of their careers. Meanwhile, the ten-day release provision allowed teams to release their players for any reason at all simply by providing them with ten days notice.

The Federal League's attorneys believed that these two provisions, taken in combination, rendered the players' contracts legally unenforceable due to a lack of mutuality, insofar as they believed it was unfair to force a player to work for a single team for his entire career when the team itself was bound to the player for no more than ten days at a time. The Federal League's position was supported by several legal decisions arising out of the so-called Players' League challenge of 1890, in which courts refused to enforce the reserve clause in players' contracts. See Metropolitan Exhibition Co. v. Ward, 9 N. Y. Supp. 779 (Sup. Ct. 1890); Metropolitan Exhibition Co. v. Ewing, 42 Fed. 198 (C. C. S. D. N. Y. 1890). Based on this legal theory, the Federal League successfully persuaded approximately 50 major league players to sign with it during the 1913-14 off-season.

The major leagues fought back by aggressively recruiting the defecting players back into their fold, often offering the players significant raises. Ultimately, thirteen different lawsuits were filed between the two sides in 1914, as the parties sought injunctions to prevent their players from jumping back and forth between the leagues. While devoted students of baseball legal history may have already been aware of several of these cases, including Cincinnati Exhibition Co. v. Marsans, 216 F. 269 (E.D. Mo. 1914), Weeghman v. Killefer, 215 F. 168 (W.D. Mich. 1914), and American League Baseball Club of Chicago v. Chase, 149 N.Y.S. 6 (Erie County Sup. Ct. 1914), others had been largely forgotten prior to my research.

For example, one of the most significant cases of the year involved pitcher George "Chief" Johnson (pictured), who defected to the Federal League in April 1914 following a dispute with his prior team, the Cincinnati Reds. The Reds immediately secured a temporary injunction in Illinois state court to prevent Johnson from making his Federal League debut in Chicago during the inaugural game at Weeghman Park, better known today as Wrigley Field. By the time Cincinnati's attorneys reached the ballpark, however, the game had already begun, so Johnson was served with the court papers when walking off the field after the second inning.

The court eventually held a hearing several weeks later to decide whether to issue a permanent injunction preventing Johnson from playing for his new team. The Federal League was so confident it would ultimately prevail in the Johnson case that it reportedly arranged for as many as thirty-seven major league players to jump to the new league should it receive a favorable decision from the Chicago court. Unfortunately for the Federals, however, the state court judge issued a permanent injunction on June 3, 1914, upholding the standard player contract Johnson had signed with the Reds, on the basis that it must have been fair in light of the number of players who had voluntarily agreed its terms. Although this decision would be overturned on appeal several weeks later -- allowing Johnson to resume his Federal League career -- the damage had been done, as the Federal League's planned raid of the major leagues fell apart following the trial court decision.

While the initial decision by the Johnson court was a significant set-back for the Federal League, the parties ultimately battled to a draw in their 1914 litigation efforts, with both sides winning several important decisions. Perhaps more significantly, these lawsuits also set the stage for the next major phase of the Federal League's legal challenge to the major leagues, namely the federal antitrust lawsuit it filed with Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis in 1915 (to be discussed in my next post).

Baseball on Trial: The Origin of Baseball's Antitrust Exemption

1:30 PM |

Labels:

Baseball on Trial

I recently spent the better part of a year and a half researching and writing a book documenting the history of the 1922 U.S. Supreme Court case of Federal Baseball Club of Baltimore v. National League, the litigation that gave rise to baseball's antitrust exemption. I am happy to announce that the book, titled Baseball on Trial: The Origin of Baseball's Antitrust Exemption (from the University of Illinois Press), has been released and is now available for purchase.

Baseball on Trial draws upon a variety of original source materials, including the original court records from the litigation, contemporaneous newspaper accounts, and a recently released collection of attorney correspondence from the case available at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Research Library in Cooperstown, New York. Not only does the book document the history of the Federal Baseball lawsuit itself, but it also covers the many precursor cases arising out of the Federal League challenge to Major League Baseball in 1914 and 1915, litigation which in many ways set the stage for the Supreme Court proceedings. Through a series of posts over the next several days, I'll be summarizing some of the more interesting findings from my research.

In the meantime, here is the publisher's official description of the book:

Baseball on Trial draws upon a variety of original source materials, including the original court records from the litigation, contemporaneous newspaper accounts, and a recently released collection of attorney correspondence from the case available at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Research Library in Cooperstown, New York. Not only does the book document the history of the Federal Baseball lawsuit itself, but it also covers the many precursor cases arising out of the Federal League challenge to Major League Baseball in 1914 and 1915, litigation which in many ways set the stage for the Supreme Court proceedings. Through a series of posts over the next several days, I'll be summarizing some of the more interesting findings from my research.

In the meantime, here is the publisher's official description of the book:

The controversial 1922 Federal Baseball Supreme Court ruling held that the "business of base ball" was not subject to the Sherman Antitrust Act because it did not constitute interstate commerce. In Baseball on Trial, legal scholar Nathaniel Grow defies conventional wisdom to explain why the unanimous Supreme Court opinion authored by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, which gave rise to Major League Baseball's exemption from antitrust law, was correct given the circumstances of the time.

Currently a billion dollar enterprise, professional baseball teams crisscross the country while the games are broadcast via radio, television, and internet coast to coast. The sheer scope of this activity would seem to embody the phrase "interstate commerce." Yet baseball is the only professional sport--indeed the sole industry--in the United States that currently benefits from a judicially constructed antitrust immunity. How could this be?

Using recently released documents from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, Grow analyzes how the Supreme Court reached this seemingly peculiar result by tracing the Federal Baseball litigation from its roots in 1914 to its resolution in 1922, in the process uncovering significant new details about the proceedings. Grow observes that while interstate commerce was measured at the time by the exchange of tangible goods, baseball teams in the 1910s merely provided live entertainment to their fans, while radio was a fledgling technology that had little impact on the sport. The book ultimately concludes that, despite the frequent criticism of the opinion, the Supreme Court's decision was consistent with the conditions and legal climate of the early twentieth century.

"[A] thoughtful and provocative analysis of one of the most controversial topics in sports law: Baseball's antitrust exemption. Grow adroitly connects recent disclosures from the Baseball Hall of Fame to advance his argument that the Federal Baseball holding made much more sense ninety years ago than contemporary commentators tend to regard it. As baseball's antitrust exemption continues to face legal challenges--including whether the Oakland A's can move to San Jose--Grow's book will undoubtedly play an influential role." -- Michael McCann, Sports Illustrated legal analyst

"The lawsuits arising from the Federal League's challenge to Major League Baseball and their aftermath defined much of the way baseball has evolved over the past century. Bolstered by original research, Grow explains both the broader picture and the intriguing behind-the-scenes machinations, and he does so in a clear and entertaining fashion." -- Daniel R. Levitt, author of The Battle that Forged Modern Baseball: The Federal League Challenge and Its Legacy

"An outstanding book based on previously unused materials, Baseball on Trial makes a truly significant contribution to the fields of baseball and the law, sports law, antitrust law, and legal history. Anyone discussing the trilogy of Supreme Court cases that created baseball's antitrust exemption needs to read this book." -- Edmund P. Edmonds, co-editor of Baseball and Antitrust: The Legislative History

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)